Is the stratospheric success of one African American a form of activism? Is an individual’s ability to defy the odds and defeat institutional racism an act of heroism?

And what if those achievers aren’t all that interested in helping others reach those same heights?

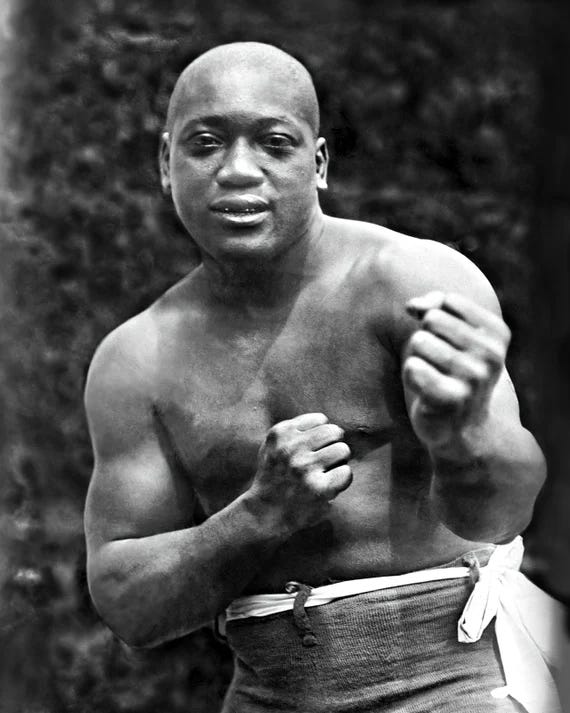

It’s a question I think about whenever anyone brings up Jack Johnson, a boxer who in 1908, became history’s first Black world heavyweight boxing champion.

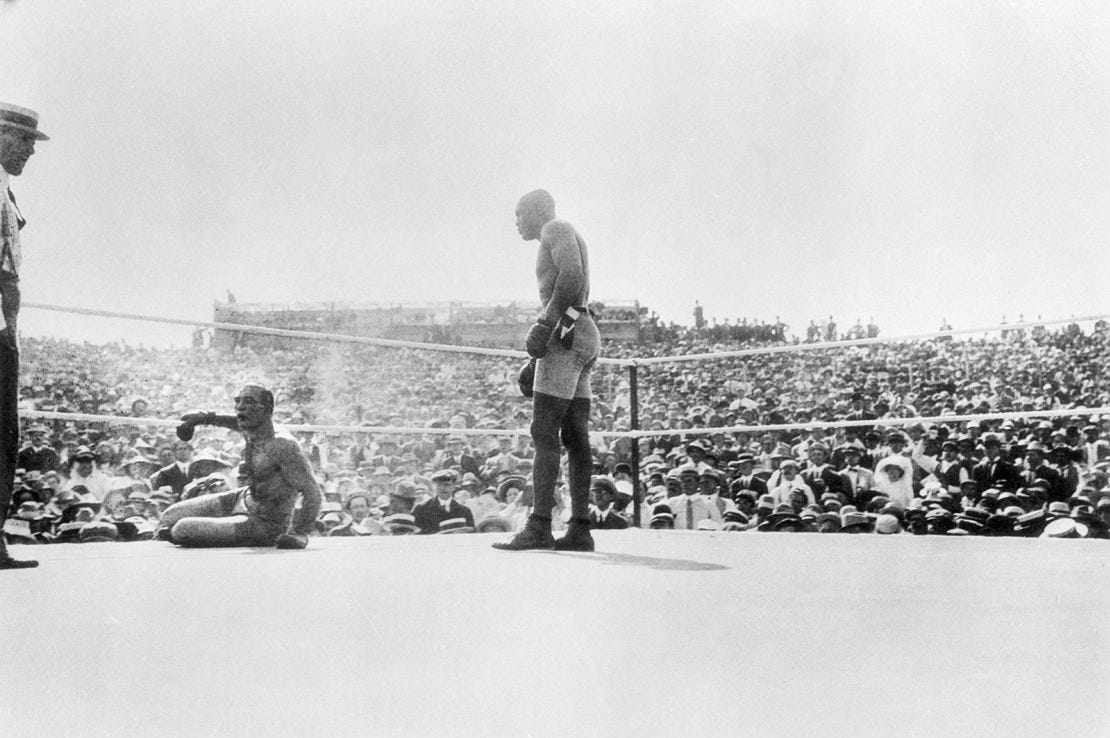

How extraordinarily cathartic it must have been for African Americans all over the country to see a Black man literally deliver a knockout blow to white supremacy. As they stood amongst the smoldering ashes of the North’s promises of civil rights, what must it have meant to the Black community to see Jack Johnson strut into the ring and assert his dominance while a white man, bloodied and shamed, gazed up at him in defeat.

And Jack Johnson only delivered blows to white men because once he became a world champion he refused to get in the ring with other African American fighters. He knew he would make more money that way. The rise of other boxers of his race could only hurt his career. He had to be singular in his achievement.

Jack Johnson didn’t set out to break a glass ceiling. Instead his goal seemed to be to take out a glass cutter and use it to make an access door for himself that he could easily close behind him.

But watching him fight, seeing his swagger, reading the reports of how he refused to defer to white men in or out of the ring…that gave the Black community a deserved sense of pride. It reminded them that they were not “less-than.” And every time Johnson refused to live the subservient, modest life that pre-Civil Rights America expected him to live, he was putting a glaring spotlight on the lie of white supremacy.

His victories inspired African American youths to take up boxing. Many of them were good. Some were great. A few went on to become champions themselves.

Jack Johnson didn’t set out to break a glass ceiling, but it broke nonetheless.

So does that make Jack Johnson an activist? A hero? A self-centered opportunist? Maybe all of the above.

I find Hattie McDaniel, a woman I feature prominently in my upcoming novel, The Great Mann, to be an equally complicated figure in Black history.

McDaniel was the first African American to win an Academy Award. Up to that point, in almost all the studio films, Black actors were treated like devices to elevate the white actors beside them. So when McDaniel, a dark skinned Black woman, beat out four highly celebrated white actresses for the most prestigious honor in Hollywood it was cause for celebration.

And McDaniel deserved it. She infused enormous amount of vitality and passion into her scenes, forcefully bringing them to life in surprising and captivating ways.

The problem is those Oscar winning scenes were in the movie Gone With The Wind, a film that was reviled within the Black community. Before it even came out there were protests against it. There were some Black journalists who praised McDaniel’s performance but many others who excoriated her for taking the role at all. African Americans of the time recognized that Gone With The Wind was a movie that romanticized an era in which their parents and grandparents were held hostage, had their children torn from their arms, were regularly humiliated, frequently raped and sometimes tortured. That’s what slavery was. That’s what The Antebellum South was for the Black population.

And Gone With The Wind was painting that pre-Civil war era as “innocent.”

Melvin B. Tolson, journalist for The Washington Tribune (an African American paper), wrote:

“The Birth of a Nation was such a barefaced lie that a moron could see through it…[but] Gone With The Wind is such a subtle lie that it will be swallowed by millions”

Slavery wasn’t a distant memory when Gone With The Wind was released as a book in 1936 or as a movie in 1939. Most African Americans had personally known a relative who had been through it.

That includes Hattie McDaniel. Both her parents had been slaves. Her father, Henry McDaniel, had escaped slavery to serve in the Union Army. He was a hero in the bloody Battle of Nashville where he fired on Confederate soldiers to provide cover for the men setting off the cannons. He continued to fire on them even after a shell exploded near his head, shattering part of his jaw. 64% of Henry McDaniel’s Black regiment died in that battle but he survived and his service was his greatest source of pride throughout his life.

Hattie McDaniel never mentioned any of that while doing press. Instead she would often talk about how her father was a preacher…which he wasn’t. But Preacher was the kind of job that was met with near universal approval by the white population and white entertainment journalists ate it up just like McDaniel knew they would.

African Americans on a whole, did not look favorably upon any of this.

And yet, there was a lot of cheering in Black households when she won that Oscar. The win meant something, regardless of what role McDaniel had to take to get it. All along McDaniel had been arguing to the Black press that she was the driver of incremental change, opening doors for other Black actors, gently pushing the studios to offer them better opportunities.

But that’s not what happened, not even for McDaniel. If anything the roles she was offered in the following years were smaller and meeker than that of Mammy. Usually she played a dim-witted maid who was there for comic relief.

She did secure one meaty, dramatic role in a movie starring Bette Davis titled In This Our Life. McDaniel’s character has some heart-wrenching scenes in which she contends with the racism within the American justice system.

But shortly after the film wrapped Pearl Harbor was bombed. America was going to war. There was no appetite for a film that offered a critique of America. In This Our Life was recut to delete scenes in which McDaniel showed any real agency or spoke of injustice.

Still, WWII provided McDaniel with other opportunities for civil activism. She formed a “Negro Division” of the Hollywood Victory Committee. She perform at USO shows, visited injured Black soldiers and appeared in a NBC tribute to their heroic sacrifices. She also provided overnight boarding for Black G.I.s who had a layover in Los Angeles on their way to serve in the Pacific Theater (most hotels in Los Angeles still wouldn’t welcome Black guests). She was appointed to the American Women’s Voluntary Service Organization and posed for publicity shots in her tailored uniform, saluting for the camera. In other PR photos she was seen giving Black soldiers tours of Warner Brothers Studios.

But those photos were for the Black press. The press kit for the white media had photos of McDaniel in her Mammy costume, smiling broadly while serving a meal to white G.I.s

This was the contradiction of Hattie McDaniel.

Langston Hughes wrote to Walter White, the head of the NAACP the following observation about Black actors like McDaniel:

“Almost any Negro—except those who play them—can spot an Uncle Tom.”

McDaniel’s business mogul neighbor, Norman O. Houston, didn’t see her so much as a traitor as he did an idiot. In his letter to Walter White he relayed his wife Edythe’s assessment of actors like Hattie McDaniel:

“…most of them are ignorant and can only fit in the parts they have been playing anyway.”

A lot of people in McDaniel’s community simply didn’t respect her.

And then, just when the criticism was almost becoming too much to bear, some of her white neighbors tried to kick her out of her house.

McDaniel lived in a mansion in West Adams Heights. Many other wealthy Black Angelenos had palatial homes in the same neighborhood. But almost all their homes had racial covenants written into the deeds which stated that no one who wasn’t purely of the white race could live in them unless they were serving as a domestic servant to white occupants. The people who had sold the homes to Black buyers had ignored the covenants but the remaining white neighbors were not inclined to do the same. They launched a lawsuit demanding that all the Black home owners be evicted from their own properties.

McDaniel had played the game. She had accepted the roles of maids and slaves, defended her movies against their Black critics and allowed the studios to lead the white public to believe she was as daft and servile as her characters. But that was meant to be part of a trade-off. In return she was supposed to be allowed a path to success and the ability to enjoy the fruits of her labor.

And here these white folks were coming for her home.

That’s when McDaniel ditched the Mammy costume and got out her mink.

After months of helping to organize the neighbors and working with the NAACP and Black civil rights attorney, Loren Miller, Hattie McDaniel put on a pair of diamond earrings and her mink coat, had her chauffeur drive her downtown and then she led the 200 hundred Black fans who were waiting for her there into the courthouse to be witness to a legal battle that would end up changing the course of history.**

She was a star.

She was an opportunist.

She was a hero.

She was self-serving.

She was a Black icon.

She prioritized her career above all.

As with Jack Johnson, I can’t tell you how you should think about Hattie McDaniel, let alone how you should feel about her.

But it’s her many complexities that made her such a dream to include as a character in my historical novel, The Great Mann.

Love her or hate her, Hattie McDaniel deserves to be remembered.

Wow! Quite thought provoking essay. This issue sounds very complicated. Are they self-centered because it is too difficult for them to show empathy?

There was a story about Clark Gable refusing to attend the Academy Awards because they refused to allow Hattie McDaniel to attend. Hattie encouraged Clark Gable to attend anyways. I could see parallels in the women's rights movement. While we have people like Gloria Steinem fighting for women's rights, there are women who benefited in terms of being allowed to vote, attend law school or become doctors - AND they donate money to anti women groups. I remember a Spanish film WOMEN ON THE VERGE OF A NERVOUS BREAKDOWN where this "feminist" lawyer turned out to be for women's rights for herself, not other women. And she refused to help this woman who needed her help.